Should newspapers get into the online learning business?

Digital strategist Amy Webb floated the prospect at October's Online News Association conference as one of the top 10 tech trends for 2014 for media companies. As massive open online courses (MOOCs) gain traction, Webb suggested that media companies should get in the game, proposing a hypothetical Washington Post University in which newsroom staff would repackage coverage into educational modules.

But the notion isn't actually hypothetical at all. Two of the country's biggest and most important newspapers, The Washington Post and The New York Times, have tried launching online education models. Lessons learned by their experiments could point the way forward to a lucrative approach to the business.

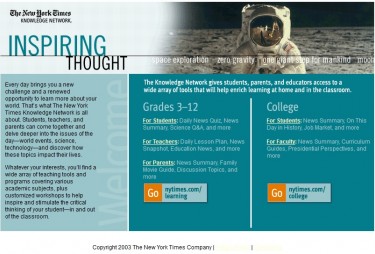

In 2011, the Post launched MasterClass, a series of online courses featuring editors and reporters as virtual instructors in disciplines such as wine, photography and the federal budget. The Times entered the online learning space even earlier. In 2007, a division of the newspaper created the Knowledge Network, which included a bevy of online classes and partnerships with a small number of universities who agreed to award certificates to participants and, in some cases, provide class credit. Many classes made use of Times content in a range of subjects from the European Union to nanotechnology.

Neither was a runaway success. But the former head of the Times' program, Felice Nudelman, now chancellor of Antioch University, a private university with campuses in Washington, California, Ohio and New Hampshire, says there are lessons to be gleaned from the pioneering programs and that now might be an even better time for news organization to take on online learning. Growing acceptance of online learning coupled with a newfound emphasis on repurposing quality content are major forces at play. Also, both the news and higher education industries share a common experience of major disruption, and both are now searching for ways of remaining essential and profitable in the digital age.

"It's almost a no-brainer," she says. "News organizations and educational institutions are absolutely aligned in terms of the potential for partnership and in meeting similar needs. You have news organizations that have incredible treasure troves of content. Historically, they've worked with academic institutions, and it's not a foreign leap to say 'Why don't universities and news companies do this together."

Rick Edmonds, media business analyst for the Poynter Institute, is less optimistic than Nudelman, but says that media companies like the Post with some experience in education have a strategic advantage when it comes to trying to make online learning stick.

'It is certainly a fit to the current imperative that media companies try new things digitally and see whether they can build some momentum — or if not shut that initiative down and try something else,' Edmonds says.

Candy Lee, who was the chief advisor and developer of MasterClass, has left the Post and is now a journalism professor at Northwestern University and an instructor in content strategy on Coursera, a platform that enables users to take free online classes from 80-plus top universities. She deferred questions about the program to her former employer, which declined to comment for this story.

The MasterClass website is still live, only courses have been discounted drastically from $400 to $69.95 each. The seven courses featured in the online catalog include one on China taught by award-winning journalist John Pomfret, an economics literacy class by Post columnist Steven Pearlstein and a class about the fact and fiction of the espionage world by columnist David Ignatius.

For each course, participants sign up and pace the lessons at their leisure. Teachings include video, multimedia images and case studies to read. According to the site, each class takes 10 to 25 hours total, and people who sign up for classes have six months to finish the instruction. Even though the modules have been set up ahead of time, participants reportedly can get access to the instructors along the way for questions and assistance.

The Times’ version of an online learning initiative, which lasted for five years, has a few key differences.

Because the Knowledge Network involved working with colleges and universities, the primary way of making money was a revenue share with the partner institutions. The Post built its system on its own and generated revenue solely from students' course fees. Also, thanks to the partnerships, the Times ' course subjects tended to be less lifestyle-driven and more tied to academic areas of study. Many of the courses could also be taken for credit with partner universities.

In Nudelman's experience, the more the courses are tied to someone's area of study or career, the better the participation and retention.

Though Nudelman would not share financial data about the Knowledge Network, she says a number of the courses had high participation numbers and were very well received.