It’s a long way from New York’s Madison Avenue advertising agencies to Gaborone, but for Botswana a lot is riding on the success of the ad campaign De Beers will launch in the coming weeks.

Like oil-exporting countries now mired in deficits because their annual budgets were predicated on oil priced at $100 a barrel that’s now well below $50, Botswana faces a similar conundrum created by a drop in the sale and prices of its rough diamonds. Diamonds account for about a third of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), 80 percent of exports and 40 percent of the entire government’s revenues.

Last week, Botswana’s Ministry of Finance cut its GDP growth forecast for 2015 to 2.6 percent from an earlier projection of 4.9 percent. The treasury also revised its budget to post a deficit as a percentage of GDP to 1.1 percent for fiscal year 2015/16 rather than the surplus initially touted.

“The downside risk to these projections continues to be the country’s high dependence on diamonds, whose demand and prices are subject to global fluctuations,” the ministry wrote in a 2016/17 budget-strategy paper published September 11.

Lower Exports, Production

Botswana has had some recent success in diversifying its economy with the treasury reporting that growth in non-mining outpaced its mining sector in 2014. However, the downturn in diamond demand and prices and its consequent effect upon the nation’s income, serves as a reminder that it is still very reliant on the mining of precious stones and, in particular, De Beers. An estimated 80 cents of every dollar of the company’s rough sales is channeled to the government, which holds a 15 percent stake in De Beers, and with whom it is also an equal partner in the mining corporation Debswana and sorting house DTC Botswana.

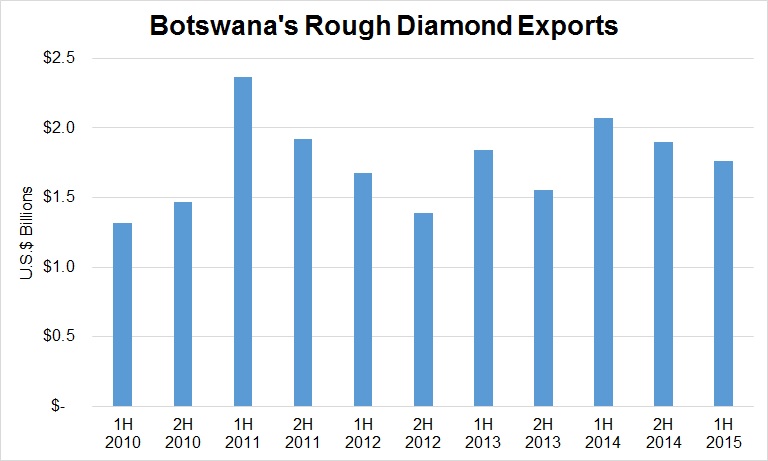

As De Beers sales have slumped, the country’s rough exports dropped 15 percent year-on-year to $1.7 billion in the first half of 2015, according to Bank of Botswana (see graph below). Overseas shipments are expected to hit a five-year low in the second half as De Beers sales fell further in July and August and the prognosis is for the decline to continue for the rest of the year.

Economists see the decline in diamond production as a key indicator of growth as Debswana’s output slid 4 percent to 12 million carats in the first six months. The fall has a wider impact on economic growth as production is an important component of the nation’s GDP calculation, Keith Jefferis, the managing director of econsult Botswana and former deputy governor of the Bank of Botswana, said.

De Beers has cut its planned output for 2015 to between 29 million and 31 million carats from an initial projection of about 34 million carats. The bulk of this reduction is expected to come from Debswana, which accounts for two-thirds of the De Beers total. Debswana’s secretary for economic and financial planning Taufila Nyamadzabo said the company has cut its 2015 production target to 20 million carats from 23 million carats, according to a Reuters report. Consequently, Rapaport estimates that Debswana’s second half production will decline by 31 percent to about 8.5 million carats.

Prolonged Downturn

For now, Jefferis is not too concerned about the budget as he noted the government has a healthy current account and balance of payments surplus as well as sufficient foreign currency reserves to see it through 2015. Botswana has benefited from two bumper years in diamond mining which stimulated GDP growth to 4.4 percent in 2014 and 9.3 percent in 2013. Furthermore, the 2.6 percent growth and slight deficit forecasted for this year is not that bad in today’s economic reality. Next year, he stressed, will be a different story and more challenging if the dip continues – which some pundits believe is likely.

“We see risks for an even more pronounced deficit because of a prolonged downturn in world diamond demand tied to China’s economic rebalancing and lower luxury spending,” analysts at Moody’s Investors Service said in an August 27 note. “Given the weight of diamond revenues in the budget, an extended global slowdown would erode the current account surplus and make fiscal consolidation an essential component in its policy mix.”

Consequently, the government is being forced to prioritize spending as it tackles unemployment and poverty in the country. The treasury said it will give precedence to ongoing critical projects in areas such as water, power generation, roads, bridges and airport construction, as well as information and communications technology.

One can’t help but acknowledge the success of Botswana’s infrastructural endeavors hinge on the long-term growth of its diamond industry. As Onkokame Kitso Mokaila, Botswana’s minister for minerals, energy and water resources, noted at a Rapaport Breakfast seminar in Las Vegas in June 2014: “Every Botswanan benefits from the impact of the diamond industry, be it through health subsidies, water, education or infrastructure.”

Rethinking Strategy

In fact, Botswana’s dependence on diamonds has arguably increased in the past few years driven by its Diamond Hub program to diversify the downstream diamond segment. De Beers relocated its sorting and sightholder sales from London to Gaborone and the state-owned Okavango Diamond Company was established to sell 15 percent of Debswana’s production independently of De Beers. Those developments brought a hike in diamantaire traffic to Gaborone, which also stimulated growth in the nation’s hospitality, construction and transportation industries. The government has also successfully leveraged its supply of rough to build a now well-established diamond manufacturing sector.

However, an estimated 1,000 jobs have been slashed in diamond cutting and polishing in the past year as manufacturers have scaled down operations, Jacob Thamage, Botswana’s Diamond Hub program coordinator, told Rapaport News. Two stalwarts of the local polishing sector have closed down, namely Teemane Manufacturing Company and Diamond Manufacturing Botswana. At the same time, KGK Diamonds recently opened a facility. Today, there are 20 De Beers sightholders with operating factories in Gaborone employing about 2,600 people.

For a country with an estimated 20 percent unemployment rate within a population of just under 2 million, the need for job opportunities as well as the expectation – and importance – of generating additional economic activity around the diamond industry cannot be underestimated.

Thamage stressed that while government has by no means abandoned the Diamond Hub program, the decline in global demand has certainly slowed its plans. With the next phase of that plan aimed at developing advanced jewelry manufacturing in Botswana, the country may be better served by jewelers investing in marketing and sales in New York and Beijing than building new factories in Gaborone at this point.

After all, the government clearly recognizes the trickledown effect that weaker global diamond demand still has on its economy via mining output, diamond manufacturing and rough trading, ultimately impacting the nation’s ability to further diversify. Thamage acknowledged the government is closely monitoring jewelry sales in the coming holiday season and he welcomed De Beers decision to invest again in generic marketing to complement its ‘Forevermark’ campaign this season.

“Like everyone, we’re waiting to see what the Christmas season will be like,” he said. “If things don’t improve, we’ll have to go back to the drawing board and rethink our strategy.” Simply put, as De Beers rolls out its ‘Diamond is Forever’ message to a new generation of consumers, its success has immediate and long term implications for Botswana.