Analyst: existing solar tech to miss 'SunShot' goal 25 Sep 2013 Lux Research says that large corporations must partner with academia to innovate.

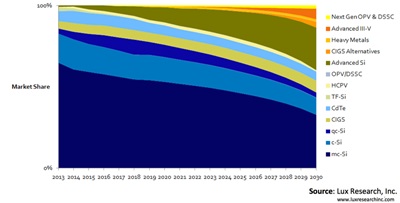

PV adoption roadmap through 2030

The US Department of Energy's ambitious "SunShot" mission to reduce the cost of solar photovoltaics dramatically by 2020 will miss its $1 per Watt price target – and it will be at least 2030 before technology meets the goal.

That's according to the cleantech analyst company Lux Research, which also says that with a dearth of venture funding in the sector, large companies need to partner with academia in order to gain access to the kind of innovation that could reduce the cost of PV to SunShot levels.

Launched by then-energy secretary Steven Chu back in February 2011, the SunShot initiative has allocated millions of dollars of research funding to groups working on reducing the cost of PV. In the meantime, the cost of PV has indeed plunged – though more as a result of market forces caused by huge oversupply rather than new technology.

Even so, PV remains more expensive than conventional energy in general. And with PV prices now stabilizing as Darwinian economics continues to take its toll on the sector, future price reductions will instead be brought about by innovations such as more efficient light conversion.

Lux says that today's solar installation prices remain between two times and four times the SunShot targets of $1/W for utility projects, $1.25/W for commercial, and $1.50/W for residential.

"Even in 2030, improvements will leave installation prices 13% above the targeted $1/W utility installation price," the Boston-based analyst firm predicts.

Bifacial cells lead the way

In her report, Lux's Fatima Toor identifies bifacial crystalline silicon modules, followed by tandem cell architectures for III-V and CIGS technologies as the three approaches that will come closest to the target module costs and efficiencies by 2030.

"Other technology families such as OPV/DSSC (organic photovoltaics and dye-sensitized solar cells) and heavy metals are likely to be farther away," Poor added.

And with private investors scared off by the large number of expensive PV failures that they have suffered over the past couple of years, bringing about the necessary innovation will require a different approach.

"With the gloomy solar venture capital funding [situation] for start-ups, it is time for large corporations to partner with academic and government research institutions to access the photovoltaic innovation landscape," states the Lux report.

It looks at the innovation taking place in research labs around the world in five different PV technology families: crystalline silicon; copper indium gallium (di)selenide (CIGS) alternatives; heavy metals, III-V semiconductor technologies, and organic photovoltaics and dye-sensitized solar cells (OPV/DSSC).

The analyst team reckons that advanced silicon technologies will remain the leader in terms of cost per watt, and maintain market share until 2020, but that none of the approaches will hit the SunShot targets.

Changing innovation landscape

The report also finds that China has taken over from the US as the global leader in terms of intellectual property generation – hardly surprising given the market domination of Chinese manufacturers that has seen numerous Western rivals driven out of business.

Thanks to the rise of leading Chinese solar manufacturers, the likes of Trina Solar and JA Solar, China actually reached that position as long ago as 2009. Korea now stands third, behind the US and ahead of the combined European Union countries, Taiwan, and then Japan.

"Lower VC funding is transforming the innovation landscape," Lux added. It says that VC funding for the solar industry has slumped from 86 deals at the 2008 peak to just 34 in 2012.

With start-ups far less likely to find backing from burned investors to commercialize new technologies, the route to PV innovation instead lies in partnerships between academic and government institutions and large corporations.

Lux says that five research institutions lead the way when it comes to corporate partnerships: Belgium's IMEC microelectronics development center, Georgia Tech, the University of Delaware, the Netherlands-based ECN, and Arizona State University.

It found that IMEC led in tie-ups with chemicals and materials manufacturers, while ECN and Georgia Tech focused on materials suppliers and equipment manufacturers active in crystalline silicon.