Ordinary fishing line and sewing thread have joined forces in the lab to create incredibly strong artificial muscles. The new artificial muscles could someday lend superhuman strength to robots and wearable exoskeletons for humans.

The twisted, coiled combinations of polymer fishing line and sewing thread can lift 100 times more weight and have 100 times greater mechanical power than the same length and weight of human muscle. U.S. researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas worked with colleagues from Australia, Canada, China, South Korea and Turkey on the breakthrough detailed in the 21 February 2014 issue of the journal Science.

"The application opportunities for these polymer muscles are vast," said Ray Baughman, the Robert A. Welch Distinguished Chair in Chemistry at UT Dallas and director of the NanoTech Institute, in a news release. "Today's most advanced humanoid robots, prosthetic limbs, and wearable exoskeletons are limited by motors and hydraulic systems, whose size and weight restrict dexterity, force generation, and work capability."

A bundle of fishing lines with a total diameter just 10 times wider than a human hair can create an artificial muscle capable of lifting over 7 kilograms, Baughman said. If combined in parallel like biological muscles, 100 of the artificial muscles could lift about 0.7 tonnes. The muscles can also generate about 7.1 horsepower per kilogram, or the equivalent mechanical power of a jet engine.

The twisted polymer fibers have enough torsional power to spin a heavy rotor more than 10 000 revolutions per minute when heated. Additional "extreme" twisting creates coiled artificial muscles that can either contract or expand along their length when heated, depending on the direction of the twist. These coils can contract by about 50 percent of their length—much more than biological muscles, which can contract by about 20 percent.

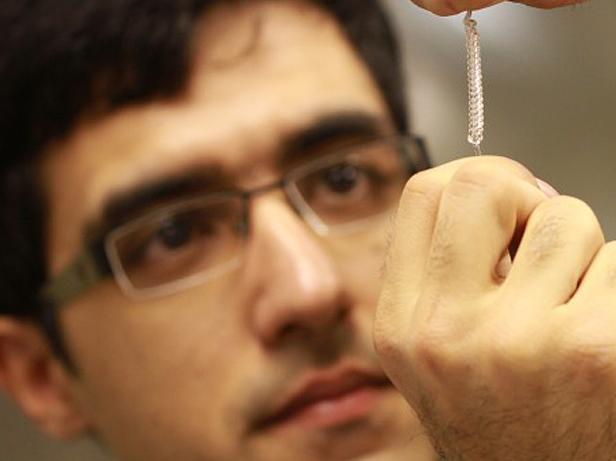

Such artificial muscles are usually electrically powered by resistive heating, said Carter Haines, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering at UT Dallas and lead author on the new study. The resistive heating can come from the metal coating of commercial sewing thread or from metal wires twisted together within the coiled muscles. But the muscles can also draw power from environmental temperature changes.

The new muscles could benefit technologies beyond enhancing the strength of future robots or robotic exoskeletons. Smaller bundles of the polymer muscles with a diameter thinner than a human hair could give life to more nuanced facial expressions in humanoid robots, or lend a precise touch to robotic microsurgery on the tiniest levels.

Researchers also envision the new muscles replacing typical motors in smart buildings with windows that automatically open and close in response to temperature changes, or powering tiny lab-on-a-chip devices.

The UT Dallas team led by Baughman previously experimented with artificial muscles based on carbon nanotubes twisted into bundles and infused with paraffin wax. But their latest work with the fishing line and sewing thread shows that even relatively mundane materials may have a lot to offer.