Among the major schools of traditional Chinese embroidery, Jing Xiu handicraft is at the risk of disappearance and has been listed as works of China's own Intangible Cultural Heritage (a list ensuring that China's best culture tradition is preserved and developed as well as made known to the outside world).

Jing Xiu, also called Gongting Xiu or Gong Xiu, was originally made for the imperial household. In Chinese, Xiu means embroidery and Jing was named after Beijing, while Gongting or Gong refers to the royal palace occupied by the imperial families in old China.

The history of Jing Xiu dates back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907) when special workshops were established to produce embroidery items for the imperial household. In the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, the style of Jing Xiu took shape in terms of materials, handcraftsmanship, and embroidery patterns.

Noted for the rigid standard of counted stitch, symbolic patterns, and second-to-none skills, Jing Xiu embroidery took the lead of the Four Minor Embroidery Schools of Qing, along with the embroideries of Lu Xiu from Shandong Province, Bian Xiu from Henan Province, and Ou Xiu from Zhejiang Province.

Uniqueness

Imposing Style

Jing Xiu stands out by its strong influence in the style from the imperial qualities, an attribute that is rare in Chinese embroidery arts. The needlework features elegant colors and grandiose images, marked by rigorous specification on silk material, types of stitches, and design patterns. The whole piece spreads out the smell of dignity, nobility and masculine splendors, as opposed to the local stitch works spiced with delicacy. Although complicated in the design, the booming composition arouses no sense of lavishness but lends itself to aesthetic enjoyment.

Luxuriant Texture

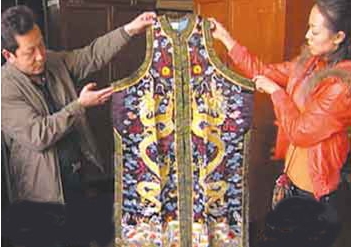

Jing Xiu was remarkably expensive concerning its material. Since it was made especially for the royalties, including the emperor and the queen, the silk material used was second to none. The needlework was basically created in choice satin, into which silver and gold thread was largely woven. Meanwhile, flying dragons and grand phoenixes constituted the major theme of the embroidered patterns, with an emphasis on absolute sovereignty and honored glory.

Male Workers

A curious character of Jing Xiu is related to its handicraft workers. Unlike other embroidered piece made by females, Jing Xiu, with a view to embody the emperorship, was commonly fashioned by skillful craftsmen.

Stringent Specification

Apart from design patterns and embroidered colors, stern requirements were also imposed on satin stitches. A case in point is the imperial robe, onto which dragon eyes, claws, and hair were embroidered with special standard in terms the number of needling, the distribution of the stitch, and the gradation of the color.

Symbolic Images

Works of Jing Xiu embroidery incorporated deep connotation. Each piece fully signified noble prosperity, sanctified power, and graded rank, as far as embroidered animals, plants, and heavenly bodies were concerned. For example, the use of a sun pattern suggested bright future and was exploited to repel evils, whereas designs of 100 butterflies implied the desire for longevity in that "100 butterflies" sound like bai die (100 years old) in Chinese.

In addition, the pattern of "the Gold Dragon with Five Flying Claws" (Wu Zhao Jin Long) represented the emperor's absolute power and therefore nobody except the emperor himself could wear the image. Besides, as Chinese peonies are acclaimed as the queen of all the flowers, they become the first choice for the empress, queen, and princess. Differing from those in local embroideries, the broidered peony in Jing Xiu featured booming contour and exaggerated shape, marked by grand dignity.

To some extent, Jing Xiu was invaluable. As signs of noble status, its practical function had little significance and Jing Xiu items were commonly made for decoration. For example, the head ornaments, the baldric, and the sabretache (a kind of pocket or pouch) were the common subjects of the embroidery goods. Sometimes, emperors gave Jing Xiu as gifts to those talented officials.

Risk for Disappearance

It is not until the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), when the imperial power dwindled, that the technique of Jing Xiu embroidery began to circulate in local regions. Since noted for its high cost, the fancywork goes beyond the average person's reach and thus strikes a painful way for maintenance. Especially at present, the expensive imperial items, magnificent but with little functional purpose, hardly fit modern taste. In consequence, the ancient superb technique is at the risk of being lost.

In 2003, a workshop of "Baigong Fang" was started in Beijing City, where China's traditional handicraft arts were exhibited including Jing Xiu embroidery. And in September of 2005, the program of China's own Intangible Cultural Heritage was launched with the purpose of preserving and passing on China's best culture tradition.