Chinese ceramic ware shows a continuous development since the pre-dynastic periods, and is one of the most significant forms of Chinese art. China is richly endowed with the raw materials needed for making ceramics.

| Chinese Ceramics range from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns, to the sophisticated Chinese porcelain wares made for the imperial court. Porcelain is so identified with China that it is still called "china" in everyday English usage. Most later Chinese ceramics, even of the finest quality, were made on an industrial scale, thus few names of individual potters were recorded. | |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Materials

Chinese porcelain is mainly made by a combination of the following materials:

- Kaolin - essential ingredient composed largely of the clay mineral kaolinite.

- Pottery stone - are decomposed micaceous or feldspar rocks, historically also known as petunse.

- Feldspar

- Quartz

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chinese Porcelain Wares in Different Times

| | | | |

| Earthenware vase, Eastern Zhou, 4th-3rd century BC | A painted earthenware tripod Western Han Dynasty | A footed earthenware lamp, from Northern dynasties or Sui Dynasty | ceramic plate with three colors, 8th-9th century |

| | | | |

| celadon bowl, 10th-11th century | A celadon shoulder pot from the late Yuan Dynasty | Porcelain vase from the reign of the Jiajing Emperor | Porcelain plate from the reign of the Qianlong Emperor |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Types

Tang Sancai burial wares

| | Sancai means three-colours. However, the colours of the glazes used to decorate the wares of the Tang dynasty were not limited to three in number. Sancai wares were northern wares made using white and buff-firing secondary kaolins and fire clays. In the West, Tang sancai wares were sometimes referred to as egg-and-spinach by dealers for the use of green, yellow and white. |

Jian tea wares

| | Jian blackwares, mainly comprising tea wares, were made at kilns located in Jianyang of Fujian province. They reached the peak of their popularity during the Song dynasty. The wares were made using locally won, iron-rich clays and fired in an oxidising atmosphere at temperatures in the region of 1300 °C. |

Ding ware

| | Ding ware was produced in Ding Xian (modern Chu-yang), Hebei Province, slightly south-west of Beijing. Already in production when the Song emperors came to power in 940, Ding ware was the finest porcelain produced in northern China at the time, and was the first to enter the palace for official imperial use. |

Ru ware

| | Like Ding ware, Ru was produced in North China for imperial use. The Ru kilns were near the Northern Song capital at Kaifeng. In similar fashion to Longquan celadons, Ru pieces have small amounts of iron oxide in their glaze that oxidize and turn greenish when fired in a reducing atmosphere. |

Jun ware

| | Jun ware was a third style of porcelain used at the Northern Song court. Characterized by a thicker body than Ding or Ru ware, Jun is covered with a turquoise and purple glaze, so thick and viscous looking that it almost seems to be melting off its substantial golden-brown body. |

Guan ware

| | Guan ware, literally means "official" ware; so certain Ru, Jun, and even Ding could be considered Guan in the broad sense of being produced for the court. Strictly speaking, however, the term only applies to that produced by an official, imperially run kiln, which did not start until the Southern Song fled the advancing Jin and settled at Lin'an. |

Qingbai wares

| | Qingbai in Chinese literally means "clear blue-white". The qingbai glaze is a porcelain glaze, so-called because it was made using pottery stone. The qingbai glaze is clear, but contains iron in small amounts. When applied over a white porcelain body the glaze produces a greenish-blue colour that gives the glaze its name. Some have incised or moulded decorations. |

Blue and white wares

| | "Blue and white wares" designate white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration is commonly applied by hand, by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. Distinctive blue-and-white porcelain was exported to Japan where it is known as Tenkei blue-and-white ware or ko sometsukei. This ware is thought to have been especially ordered by tea masters for Japanese ceremony. |

Blanc de Chine

| | Blanc de Chine is the traditional European term for a type of white Chinese porcelain, made at Dehua in the Fujian province, otherwise known as Dehua porcelain or similar terms. It has been produced from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) to the present day. Large quantities arrived in Europe as Chinese Export Porcelain in the early 18th century and it was copied at Meissen and elsewhere. Many of the best examples of blanc de Chine are found in Japan where the white variety was termed hakugorai or "Korean white", a term often found in tea ceremony circles. The British Museum in London has a large number of blanc de Chine pieces, having received as a gift in 1980 the entire collection of P.J.Donnelly |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Authentication

Chinese potters have a long tradition of borrowing design and decorative features from earlier wares.

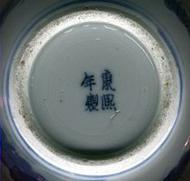

| | The leftt is Kangxi reign mark on a piece of late nineteenth century. Whilst ceramics with features thus borrowed might sometimes pose problems of provenance, they would not generally be regarded as either reproductions or fakes. The most widely known test is the thermoluminescence test, or TL test, which is used on some types of ceramic to estimate, roughly, the date of last firing. The TL test is carried out on small samples of porcelain drilled or cut from the body of a piece, which can be risky and disfiguring. |

Written by Nicolas Yang