Researchers have found a new application of 3D printing that produces lithium-ion batteries the size of a grain of sand. The batteries could some day enable the development of miniaturized medical implants, compact electronics or tiny bots.

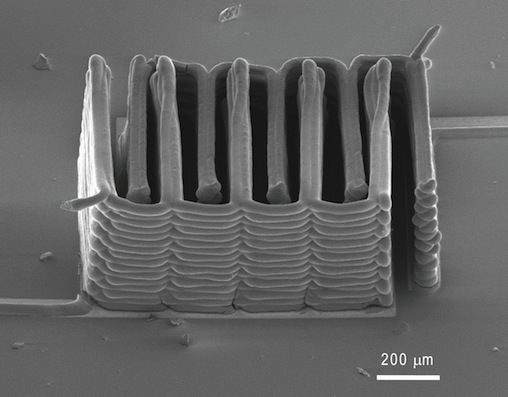

The 3D printing technology, developed by researchers at Harvard University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, was able to produce interlaced stacks of tiny battery electrodes, each less than the width of a human hair.

The researchers see the micro batteries as a possible source of electricity for tiny devices that could be used in areas ranging from medicine to communications. The batteries may also help advance uses of nanotechnology, which has lingered on lab benches for lack of a battery small and powerful enough to fit into a device, such as a miniaturized medical implant.

The results of the research were published online in the journal Advanced Materials.

"Not only did we demonstrate for the first time that we can 3D-print a battery; we demonstrated it in the most rigorous way," said Jennifer Lewis, senior author of the study and a professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Lewis led the project in her prior position at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in collaboration with co-author Shen Dillon, an assistant professor of Materials Science and Engineering there.

This image shows the interlaced stack of electrodes that were printed layer by layer to create the working anode and cathode of a microbattery. (Image courtesy of Jennifer A. Lewis.)

Nano devices invented in recent years include medical implants, flying insect-like robots, and tiny cameras and microphones that fit on a pair of glasses.

"But often the batteries that power them are as large or larger than the devices themselves, which defeats the purpose of building small," Harvard stated in a news release. To get around this problem, manufacturers have traditionally deposited thin films of solid materials to build the electrodes."

However, due to their ultra-thin design, the solid-state micro-batteries didn't have enough power for the miniaturized devices, the researchers said.

The Harvard researchers discovered they could create stacks of ultrathin electrodes by using 3D printers that followed three-dimensional computer drawings. The printers deposited successive layers of inks to build the batteries, similar to stacking a deck of cards, one card at a time.

Lewis' group designed a broad range of functional inks that have various chemical and electrical properties.

To create the microbattery, the custom-built 3D printer extrudes the inks through a nozzle that's about 30 microns in diameter -- narrower than a human hair.

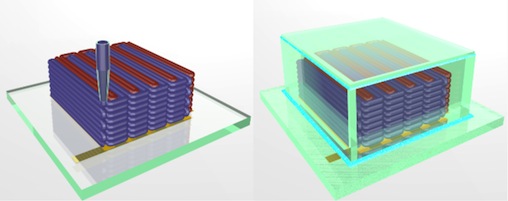

Those inks solidify to create the battery's anode and cathode, layer by layer. A case then encloses the electrodes and the electrolyte solution is added to create a working microbattery.

"The electrochemical performance is comparable to commercial batteries in terms of charge and discharge rate, cycle life and energy densities. We're just able to achieve this on a much smaller scale," said Dillon, the co-author of the research.

To create the microbattery, a custom-built 3D printer extrudes special inks through a nozzle narrower than a human hair. Those inks solidify to create the battery's anode (red) and cathode (purple), layer by layer. A case (green) then encloses the electrodes and the electrolyte solution is added to create a working microbattery. (Illustration courtesy of Jennifer A. Lewis.)

The work by the researchers was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy's Energy Frontier Research Center on Light-Material Interactions in Energy Conversion.

This article, 3D printer makes lithium-ion batteries the size of a grain of sand, was originally published at Computerworld.com.